While we don’t know much about most of the different PFAS out there, we do know that they are persistent. The thing that makes a PFAS a PFAS is the combination of carbon and fluorine, a combination which does not break down in the environment. Or if it does, no one has seen or recorded it yet.

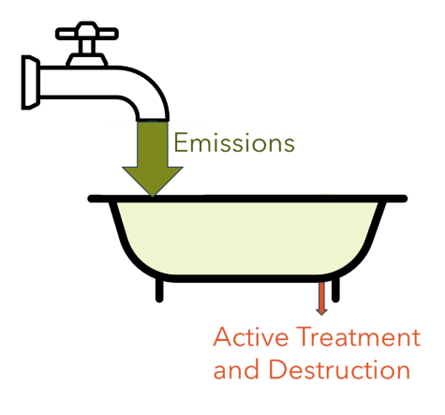

We need to start thinking about the long-term forecast for PFAS in the environment. This is where persistence (long-lasting-ness) comes in as a key characteristic. If it never goes away naturally and the only thing removing it is people spending energy and money to actively remove and destroy it, we can think of the global environment like a bathtub. If the total amount of PFAS in the global environment is like a bathtub, it’s filling up (emissions). Like with a fire hose. There is currently a tiny drain that reflects active treatment and destruction of environmental PFAS worldwide, but that’s less than 0.1% of how much we are emitting. This means that under the status quo, PFAS will continue to build up more and more, with constantly increasing concentrations in the environment and our blood, and constantly increasing potential for health risks.

What global PFAS looks like now

For context, the amount of PFAS currently being emitted globally is about one million tons per year1. One million tons may not seem like a lot – that’s about how much trash is made in Philadelphia each year. But remember that PFAS are present and regulated at parts per trillion values. If those millions of tons were all PFOA, the yearly emissions would be enough to pollute all the oceans on earth to exceed the 4 ppt new drinking water limits set this year in the United States. We clearly don’t have the capacity to treat anything near the scale of the entire world’s oceans for PFAS.

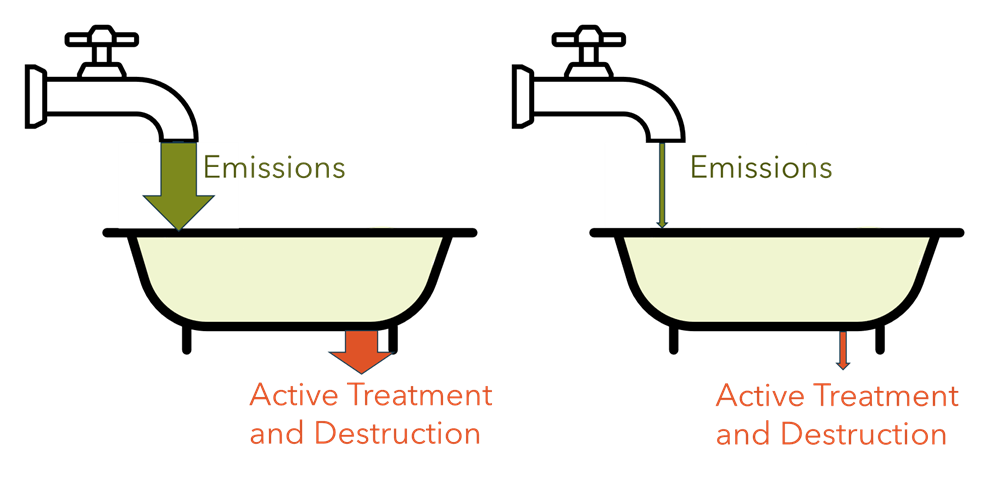

So if we are thinking long-term and don’t want continuous build-up of PFAS for future generations, we need to match what we are putting into the environment with what we are taking out and destroying. The initial response most people have to environmental PFAS is that we need to remove it from the environment. But it would cost more than the global GDP to remove PFAS from the environment at the same rate we are adding it2. It’s just not possible. It’s like trying to spend a ton of money increasing the size of the tub drain while it’s being filled with a fire hose. We need to turn the tap way down if we want to manage how much PFAS is in the environment.

What most people think we need: What’s actually achievable: (increasing treatment to match emissions) (reducing emissions a LOT)

Most of the emissions is F-gasses, with only about 1% being the more traditional PFAS we usually think of (including PFOA and other “ladder PFAS”). But just because most of the PFAS being used and emitted aren’t regulated doesn’t mean that they won’t be problematic.

There are several things we can do to reduce emissions:

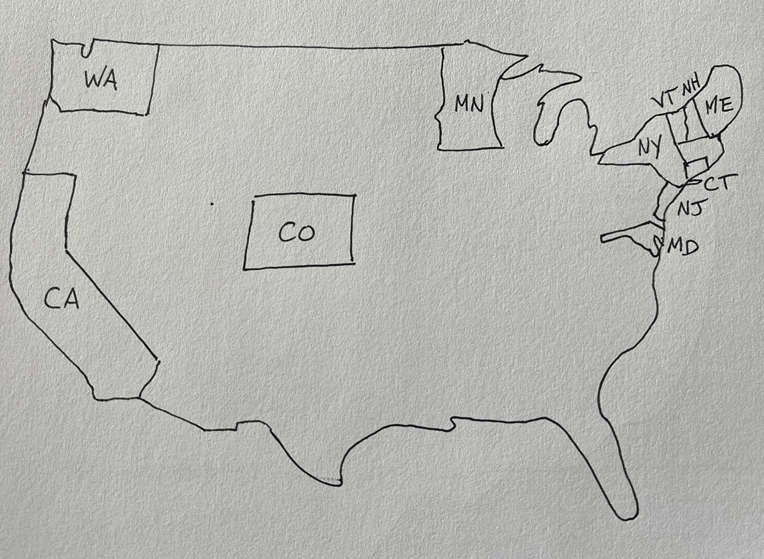

- Use less PFAS to start with. There are efforts underway in the European Union3 and in several US States, including Maine and Minnesota, to try to regulate all PFAS in all products that don’t need them.

- Destroy PFAS before it enters the environment in places where a lot of it is made and released – this includes places like PFAS production facilities.

- Do a generally better job of managing stuff with PFAS in it and limiting how much of it is released to the environment.

States with upcoming regulation to limit PFAS in products (as of early 2024)

Want the sciencey shit?

[1] Evich, M. G., Davis, M. J. B., McCord, J. P., Acrey, B., Awkerman, J. A., Knappe, D. R. U., Lindstrom, A. B., Speth, T. F., Tebes-Stevens, C., Strynar, M. J., Wang, Z., Weber, E. J., Henderson, W. M., & Washington, J. W. (2022). Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in the environment. Science, 375(6580), eabg9065. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abg9065

[2] Ling, A. L. (2024). Estimated scale of costs to remove PFAS from the environment at current emission rates. The Science of the Total Environment, 918, 170647. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.170647

[3] ECHA. (2023b). Annex XV Restriction Report: Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs). European Chemicals Agency. https://echa.europa.eu/documents/10162/f605d4b5-7c17-7414-8823-b49b9fd43aea

Leave a comment