For other places without a specific source of PFAS contamination, we don’t necessarily know how much PFAS is going into the environment and where it comes from.

PFAS from “point” sources, like factories

Some places have a lot of PFAS in the water and air as a result of specific stuff that happened there. These places with specific contamination include:

- Parkersburg, West Virginia

- Cape Fear, North Carolina

- Bennington, Vermont

- East Twin Cities Metro Area, Minnesota

We know that PFAS is made in a small number of factories (about XX companies worldwide actually make raw PFAS). Those factories send dirty water to rivers and dirty air to the atmosphere. Many of these factories are now regulated and remove some or most PFAS from dirty water or air. One factory in Fayetteville, NC used to put out 350 tonnes/year to the air before adding a machine that super-burns PFAS in the air leaving the stack. More facilities need to be doing this The same facility used to put out GenX to the adjacent river before adding treatment to remove it. The unknown here is that if it’s not regulated, it’s likely putting a lot of PFAS into the environment, but we don’t know how much. Because it’s not regulated.

And since it’s so mobile, it travels across the globe. For places without a specific source, PFAS comes from all around us.

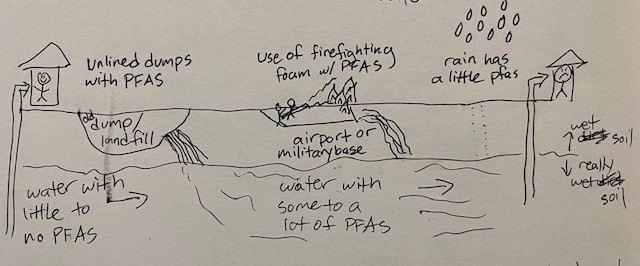

And PFAS from everywhere. . .gets into groundwater

And remember, once PFAS enters the environment, it stays there and cycles around. Lots of people are concerned about PFAS in drinking water sources these days as a result of the US publishing it’s first limits on PFAS in drinking water. But how does it get there?

We all know water comes from rain, right? Rain flows downhill to a river, or in places not totally covered by concrete, it seeps into the ground. Ground water is called “groundwater” and hangs out it then little gaps between pieces of soil or in porous rocks. Think of a wet sandbox – there’s water in between all the grains of sand. When rain also contains PFAS (as it often does these days), it follows along with the water for the ride. PFAS can also get into groundwater from buried stuff and spilled stuff that seeps into the ground with the water. PFAS can also get into groundwater from landfills or specific sources, as mentioned earlier.

We know that PFAS is in stuff that we use in houses, businesses, and other factories. Some of that PFAS stays in the product until it ends up in a landfill. Some of the PFAS wears away during dry use and sticks to household and workplace dust. Some of the PFAS wears away during washing and ends up flushed or drained to wastewater.

Flushing stuff away

When you flush your toilet or run your washing machine and all that water goes “away,” it goes to a wastewater treatment plant. WWTPs are amazing places where people and machines work hard to turn your gross toilet water and other liquids into water that’s pretty clean. Clean enough to send to your local river and not make people or fish there sick. They work great to remove things like toilet paper and other bits, nutrients like ammonia and phosphorus that make rivers and lakes all green, organic matter that removes dissolved oxygen and causes fish kills. However, your wastewater treatment plant was not designed to remove PFAS. And adding PFAS treatment would increase your sewer bill by a lot, especially if you live in a small town1. Which means that many PFAS flushed to wastewater from your washing machine and dishwasher and shower ultimately end up in the river.

Wastewater treatment is great, but isn’t designed to remove PFAS

One highly publicized way for PFAS to enter the environment is through “biosolids.” Now I know wastewater biosolids sounds like poop. But it’s actually a technical term meaning the sterilized corpses of tiny bacteria that just finished eating your poop. So now you won’t be grossed out when I tell you that we use biosolids as a fertilizer. Right? In all seriousness, biosolids are a renewable resource that have a lot of thing things that plants crave. And it makes more sense environmentally to use them as a fertilizer than to put them in a landfill, where they’ll make a lot of methane, and use artificial fertilizer, which uses a lot of energy and pollutes waterways. But since wastewater has PFAS, biosolids also have PFAS.

Throwing stuff “away”

When you throw stuff “away,” it goes to a landfill. Newer landfills have lining on the top and bottom designed to keep their insides inside. But landfills are constantly oozing landfill juice (called leachate) that’s full of nasty stuff and also has PFAS. This leachate sometimes goes to wastewater treatment, but most in many places it either is sent back into the landfill or leaks into the groundwater. PFAS can also escape landfills in the gas, probably in similar quantities to how much leaves in leachate.

Want the sciencey shit?

[1] Ling, A. L., Vermace, R. R., McCabe, A. J., Wolohan, K. M., & Kyser, S. J. (2024). Is removal and destruction of perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances from wastewater effluent affordable? Water Environment Research, 96(1), e10975. https://doi.org/10.1002/wer.10975

[2] Lin, A. M., Thompson, J. T., Koelmel, J. P., Liu, Y., Bowden, J. A., & Townsend, T. G. (2024). Landfill Gas: A Major Pathway for Neutral Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substance (PFAS) Release. Environmental Science & Technology Letters. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.estlett.4c00364

Leave a comment