The main thing you probably hear about PFAS is that they are toxic. And yes, we know that some can PFAS negatively impact our health1. But for most PFAS, we don’t have much data on how toxic they are or how much risk there is for them to get into our bodies. However, even if they are just a little toxic, there are other problematic things about them that amplify the potential health risks, both for us now and for future generations.

Four main things make PFAS especially difficult to deal with. They are 1) mobile, 2) persistent, 3) useful, and 4) numerous. Each of these characteristics map to a different difficulty in dealing with PFAS. TL/DR: Mobility makes them get everywhere, persistence makes them difficult to destroy, utility makes them difficult to phase out of the stuff we use, and the staggering number of them make them difficult to regulate. More on each below.

- Mobile = doesn’t stay put

PFAS are all over the environment. They get into the air when they are made and not removed in factory stacks, or when anyone heats or burns them (think cooking with Teflon pans on high, or garbage incinerators). They get into the water when you use stuff with PFAS in your house and flush it down the toilet or washing machine drain, or when factories that make them send them down the drain, or when they wash off agricultural fields. Being “mobile” means that they like stay in the air and in the water, so that they continue to move around. That could be moving around in the air across cities and across continents, or moving around in the water down rivers and across oceans. It means that when you bury them in landfills, they come back out in gas and water leaving the landfills.

The problem with mobility is that once they get into the environment (and we are putting millions of tonnes of them into the environment each year), they refuse to stay put in some inert place like the ground or the ocean floor2. They keep moving around in places where people can come into contact with them.

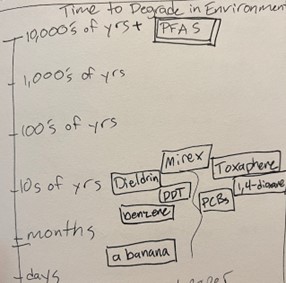

2. Persistent = difficult to destroy

PFAS are a family of chemicals, whose defining feature is a carbon atom (a C) surrounded by fluorine atoms (F’s). The C-F bond is the strongest in chemistry, which makes PFAS really useful in products, and a real pain in the butt to get rid of. It’s like the C’s and F’s are tied together with the strongest material known, so to hack it apart, you need to heat it twice as hot as your oven’s clean cycle or blast it with some other equivalent form of energy. This “persistence” contributes to the fact that there is no known way for PFAS to become not-PFAS in the environment. There are many ways to turn PFAS into other PFAS. But breaking down the last C-F bonds has not been observed to occur naturally. This means that any PFAS we put into the environment will stay there. Forever.

Adapted from 3

Ok, the engineers out there will tell you that you can break PFAS down using engineered systems. These use some combination of high temperatures, pressure, electricity, chemicals, and other types of energy to break the bonds (see more about forever/not here). They can be really useful in situations where we want to clean up a specific place or a source of PFAS. But the volume we can engineer away is currently insignificant compared to how much we are putting in the environment.

The problem is that we are making so much of the stuff, that there removing it from the environment as fast as we are adding it would cost more than the global GDP4. So we quite literally cannot afford to manage environmental PFAS through treatment. If we want less PFAS in the environment, we need to make and use less of it.

3. Useful and ubiquitous = hard to phase out of stuff we use

Gosh, these things are useful. The engineers that invented them weren’t trying to kill people or cause mass panic. They were trying to make your lives easier. PFAS can do things like keep stuff from sticking, protect your stuff from water and grease, protect you and your stuff from high temperatures, put out tricky fires that can’t be put out with water. The fact that they are so useful will make them especially difficult to phase out.

Some context on stuff we’ve phased out before:

- Chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) – remember old styrofoam and the hole in the ozone layer? We phased out CFCs, which were mostly used in cooling fluids. Joke’s on us though – we mostly replaced them with a type of PFAS.

- Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) – these were like the PFAS of thirty years ago. We phased them out in the US, largely because their use was restricted to electrical stuff and they were SUPER toxic.

Unlike those two examples, PFAS are nearly universal in products that we use. I guarantee you that you’ve used something with PFAS today. More on what those types of products are in a future post. . .

Luckily, a recent study found readily available replacements for 210 out of 261 product areas where PFAS are used5. We just need to up the incentives and R&D to actually get them phased out.

4. Numerous = hard to measure and regulate

You’ve probably heard about PFOS and PFOA. People define PFAS in different ways, but there are somewhere between 10,000 and a million different PFAS. (see more here) At that level, it doesn’t really matter how many – it’s a helluvalot. Most of them can’t be measured, and many of them can’t be effectively removed from water or air once they get there. They fact that there are just so many and they are hard to measure means that they are really hard to regulate. (For context, there are 209 PCBs. Still a lot, but more manageable and measurable.)

So what does it mean that the US is regulating six specific PFAS in drinking water? It means that we are regulating six out of thousands of these problematic compounds and ignoring the rest. At least for now. An alternative would be to regulate “PFAS as a class,” which is what the European Union is moving toward. But again, it’s hard to regulate what you can’t measure.

Oh no!!! Should we just give up now???? Probably not. If we quit just because stuff was hard, we wouldn’t get very far, would we?

Similar to many aspects of medicine, prevention is more cost effective than curing a disease once it’s started. In medicine, reducing your risk of heart disease through lifestyle changes is better and cheaper than managing heart disease once it’s begun. Similarly for PFAS, phasing PFAS out of most consumer products is cheaper than removing them from the environment once released. But prevention is hard, and medical insurance usually doesn’t cover it. It’s not a “procedure,” something we can make a big to-do about. Similarly with PFAS, it’s sexier and there’s more money to be made in treating PFAS that’s already in the environment than in phasing out their use.

Want the sciencey shit?

[1] National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2022). Chapter 3: Potential Health Effects of PFAS. In Guidance on PFAS Exposure, Testing, and Clinical Follow-Up. The National Academies Press. http://nap.nationalacademies.org/26156

[2] Evich, M. G., Davis, M. J. B., McCord, J. P., Acrey, B., Awkerman, J. A., Knappe, D. R. U., Lindstrom, A. B., Speth, T. F., Tebes-Stevens, C., Strynar, M. J., Wang, Z., Weber, E. J., Henderson, W. M., & Washington, J. W. (2022). Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in the environment. Science (WOW THIS REALLY IS SCIENCEY!), 375(6580), eabg9065. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abg9065

[3] Li, L., Chen, C., Li, D., Breivik, K., Abbasi, G., & Li, Y.-F. (2023). What do we know about the production and release of persistent organic pollutants in the global environment? Environmental Science: Advances, 2(1), 55–68. https://doi.org/10.1039/D2VA00145D

[4] Ling, A. L. (2024). Estimated scale of costs to remove PFAS from the environment at current emission rates. The Science of the Total Environment, 918, 170647. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.170647

[5] Scheringer, M., Cousins, I. T., & Goldenman, G. (2024). Is a Seismic Shift in the Landscape of PFAS Uses Occurring? Environmental Science & Technology, 58(16), 6843–6845. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.4c01947